Photos By Daniel Quinajon and Keith Durflinger

On the final day of NAMM, 2002, I was roaming the Anaheim Convention center mentally celebrating another great show. We were fortunate enough to have interviewed several of the stars we had targeted and had a good opportunity to review much of the new gear that would be introduced to consumers during the coming year. I believed that we had covered most every part of the convention. And then, as life has a habit of doing, just when I thought I knew something I discovered there was another something new to learn. I found myself standing in front of a small booth that specialized in bass guitar gear. A crowd had gathered, so much so that I had a hard time seeing what the draw was. When I finally got a look, there sat two guys exchanging licks on their bass guitars. The NAMM sound police (it’s a long story!) were militant enough to have successfully muted their amps so I could hardly discern what they were playing, but being a player myself, I recognized the phenomenal chops that both had earned. And then suddenly it was over. I had caught the tail end of an impromptu jam session. I asked several of people milling around after the performance, but all I was told was, “That was Buddha!”

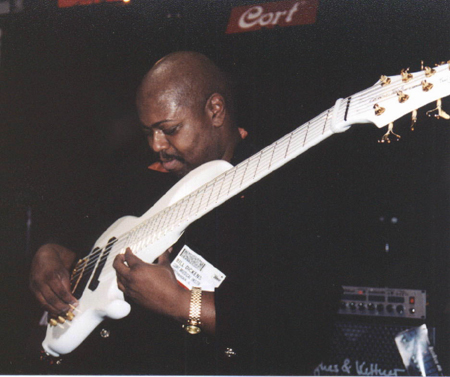

A couple hours later I came across the Cort booth and discovered once again the man they called Buddha. I found a good viewing point and, for the next 30 minutes, I witnessed a man play the bass like none other. He possessed more chops, more technique than I ever imagined possible. For me, it was a blessing and a curse. A blessing for the obvious reasons and a curse because I was ill-prepared to interview him.

Fast forward to NAMM 2003. I had a full year to research the man the called Buddha and there was no possibility that I was going to miss another opportunity to meet him.

Once again I found Dickens at the Cort booth. He was just finishing a jam with jazz guitar legend Larry Coryell. After the performance, I approached Dickens to introduce myself and arrange an interview. I shook his hand and I told him what had been on my mind since the first time I watched him play, “You’ve got the chops that others could only pretend to have!” In a very humble and peaceful way he replied, “Oh man, I just do my stuff!” After he packed up his gear, I helped Dickens haul his equipment down to the Conklin booth in the lower level of the convention center. As we were searching out a quiet place to sit down and conduct the interview, we ran into another member of the DaBelly staff, Mickie who decided to join in the fun.

Mickie opened the interview by asking about Dickens’ musical origins.

“My mom was into music,” Dickens began. “After she had me, at about six months, she started taking me to the Regal Theater (in Chicago). She would go see James Brown, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, The Supremes. I mean the whole Motown review. It was the first three years of my life. I was going every week to the Regal. The thing about it, you know, I didn’t know what was going on until I was about three. Finally, when I was able to talk, she said I would tell her that I wanted to play the instrument. I said it went ‘Boom boom boom.’ She thought I meant the drums!” Dickens’ mom took him at his word and placed him in drum lessons, learning the instrument not by ear, but by notation. He was taught to read music from the beginning. He continued drum lessons for a while, but one fateful day, Dickens found himself in a music store with his mother and for the first time was able to explain to her that the “Boom boom boom” that he wanted to play was not the drums, but rather the bass guitar. Dickens continued, “One day we went into a music store and there was this Custom bass amp and it had a bass hanging by the strap over the cabinet and I started yelling, ‘That’s the boom boom boom, mom!’ The cabinet with the head on it was over six feet and I was three and she said, ‘I’m not going to get you that!’ So she put a bass on lay-away for me. I started taking bass lessons later that year. It was so hard for me because I couldn’t get my little fingers on all the notes. So I learned on my mother’s guitar until I was big enough to play the bass.”

Dickens started performing at a very young age, but a comfortable stage presence didn’t come natural to him.

“In the sixth grade, I started playing with the school band. I played with my back to the audience. I was doing the same thing Miles Davis was doing. I was so scared. I was scared to death. I couldn’t look at an audience at all. Every time I played, my teacher would say, ‘Turn around!’ and I would just turn the other way. I started playing professionally when I was 13. I started working with some gospel groups. I had no clue who these people were. Later on, I discovered they were Rev. Johnson and James Cleveland.”

Even at an early age. Dickens was interested in the modern sounds he heard on the radio and on stage. Laughing he shared one of his earliest experiences.

“My first amp was an Ampeg 112. I remember going to see Sly and the Family Stone and I saw Larry Graham. He had this sound that was like a fuzz tone. So some time after the concert I went to a buddy’s house because we had a rehearsal. I asked him, ‘Hey man, how does Larry Graham get that sound?’ So my buddy goes and kicks my speaker in and tells me, ‘Okay, play!'”

Dickens is able to find inspiration from many performers, learning a diverse range of techniques from a wide range of artists. His unique style pays homage to an endless list of players that would be honored to have their names associated with his.

“My teacher was Monk Montgomery, Wes Montgomery’s brother,” Dickens said. “He was really a big influence on me. And then there was Freddie Hubbard, he was another one I would consider my teacher. Gene Harris, piano player, and also my buddy Henry Johnson on guitar, they were my teachers. As far as my thumb playing, there’s a guy named Steve Jennings, who I grew up with in Evanston. He was a little bit older than me, but he had the whole slap technique down in the late ’70s. I was already playing slap, but he showed me how to slap with his hands. Then I disappeared for about two years. I locked myself in the closet. The next thing you know I was playing so fast that it made no sense to me!”

Years of hard work and countless performances paid off for Dickens when he eventually found himself a member of Ramsey Lewis’s band.

“I recorded four albums with him, one was a Grammy-nominated album with the London Symphony. That was the first time I actually took a bass solo with a full 80-piece orchestra,” said Dickens. “I played for eight to nine years and, in 1990, I left Ramsey Lewis and I quit playing the bass; I became a producer. During that same period of time, I met Victor Wooten. Victor Wooten, at that time, was just a local cat in town. He had seen me on Arsenio Hall and I did a bass solo on that show. I was on the show with Ramsey Lewis. Arsenio Hall loved my solo so much that he had the show on like eight times. People from all over the country were calling me. After that, Victor found out that I had quit playing and become a producer. He kept bugging me about playing. Finally I said, ‘Okay I give!’ I started noodling around with the bass again and that led me here to NAMM.”

Curious about Dickens’ transition to playing a six string bass, I asked if it was a natural growth or more spur of the moment.

“I started around 1983 or ’84.” Dickens explained, “At the time I endorsed Ken Smith basses. Ken Smith and I were sparing partners for martial arts, karate. So every time I went to his house to spar, he would give me a gig bag with a bass in it. If I was playing in town with Ramsey, he would come to the shows. So Anthony Jackson, who was the first guy to invent the six string bass, he had made a couple of contra basses with Ken Smith. He kept one and the other went to Ken’s house. Ken showed the bass to me. When I played it, tears just rolled out of my eyes. When he told me the price, like $10,000, I said ‘Let’s see, that should take about four to five years to pay off!’ But one night when I was playing with Ramsey at a club called Fat Tuesdays in NYC, Ken came out and watched us play. I played a solo piece called ‘Willow Weep for Me.’ Ken loved it so much he asked me over to his house. He said he had another bass for me. So he gave me this bag, and I thought it was another four string bass. So I took it back to my hotel. When I pulled out the neck I noticed three keys and I thought it was a five string, but when I pulled it out, it was a six string. So I called Ken up and told him he gave me the wrong bass. He said, ‘No, that’s your bass. That’s my gift to you.’ So I started playing six string in ’83 to ’84, which gave me a little bit of fame because Anthony was the first to play the six string and I was the second and John Petitucci was the third.”

These days Dickens endorses Conklin Bass Guitars. For many years, Conklin was a custom-only bass manufacturer offering some of the most unique bass guitars ever seen on stage. The uniqueness of Dickens’ talent is a perfect match for the Conklin bass.

Dickens’ most recent tour was with Bobby Rock and Neil Zaza in support of the CD “Snap, Crackle & Pop Live.” This mixture of personalities spawned perhaps one of the most unique cover versions of the Aerosmith classic “Walk This Way.” In disbelief I had to ask, “You covered ‘Walk This Way’?”

Laughing Dickens replied, “Yes, I know. But you know, it was kind of cool because ‘Walk This Way’ is a great song. Run DMC did it and it was a huge hit. But no one had really done an instrumental version, so we recorded the song. We remained true to it, but at the same time we kind of butchered the song! We took the melody and we turned everything around. I loved doing it, it got radio play and I was happy!”

When not performing or working in any other musical capacity Dickens loves to fish. Mickie asked if he was any good and sure enough, the question invited a fish story.

“I’m good until the mosquitoes come!” Dickens revealed. “But I fish from the shore. I will not go into a boat. I went into a boat one time and got excited and the boat started tipping. Since then, I say ‘No. No thanks! No, no, no.’ I’m the guy trout, bass, sturgeon kind of guy. I like to fish on the Fox River. Actually one of my friends lives there. His house is on the lake and actually the lake goes into the Fox River. His backyard is about three miles wide and on the lake. There are thousands of fish. His dad has four to five boats. So I would get into one of the boats and he didn’t have any bait, so I would use corned beef! I knew there was a lot of fish in that lake because every time the hook hit the water, the bait was gone! So one day I got the bait and threw the hook into the lake, I caught a 15 pound bass. It was like a trophy. I was so stupid because my friend wanted to go home and cook it and I said,’ Let’s go!’ I should’ve mounted it on the wall!”

“I love fishing and I love hanging out with my son,” Dickens continues. “When I’m not doing music, I try to keep it with him. He’s a weightlifter and I love to watch him work out. I’m so into music as a producer, as a songwriter, as a technician, I don’t have much time to do some of the things that I would love to do.”

Dickens has a long list of credits, having worked with Janet Jackson, Sounds of Blackness, Debra Cox and a remix for George Michaels and Mary J. Blige and so many more. When asked about his next project, he told us about something that he has labored on for a couple of years.

“When I was out with Bobby and Neil I had a whole bunch of keyboard gear, a tape machine, so I wrote 19 songs,” said Dickens. “I started working on them when I got back to Chicago. It’s been a long process. The thing about it is I don’t want to just put out a record on my own label. Especially after having a few number one hits as a writer. I wanted my first album to be something that will make the charts. There will be some vocals on it because a bass can only go so far; bass albums don’t really sell. So there is going to be vocals, there will be guests. I’m calling all of my friends!”

Having spent a number of years in the business and several consecutive years at the NAMM convention, plus being afforded the opportunity to jam with a multitude of players, I asked, stylistically, who was the most unusual person he had played alongside.

Dickens thought for a second and then with a big smile replied, “John Entwhistle. It’s funny, I was doing a clinic at the Ken Smith booth and someone comes up behind me and covers my eyes. I kept playing and so he took his hands away and I looked around and there was this guy with a big tarantula on his chest. It was a medallion, but it was an actual tarantula! It was John Entwhistle. So I told him, ‘All I want you to do is sit down, grab that bass and play.’ We started jamming together and it was really cool.”

Mickie and I spent an hour talking to Bill Dickens that afternoon. In between funny stories about Barbara Streisand and Barry Manilow, we both discovered that monster talent doesn’t always mean monster ego. Bill Dickens is hands down one of the best bass players in music today and also one of the easiest people you will ever talk to. If you ever have the chance to see this man play, you may not immediately know his name, but within a couple of minutes you will understand why they call him The Buddha.